Buybacks, which stalled in 2022 under SEC pressure, are back in focus. This report explains how a mechanism once considered unfeasible has re-entered the market.

Key Takeaways

Hyperliquid’s 99% buyback and Uniswap’s renewed buyback discussions have brought buybacks back into the spotlight.

Buybacks, once considered unworkable, are now possible thanks to the SEC’s ‘Project Crypto’ and the introduction of the Clarity Act.

However, not all buyback structures are viable, confirming the core requirement of decentralization remains essential.

1. Buybacks Return After Three Years

Buybacks, which disappeared from the crypto market after 2022, are re-emerging in 2025.

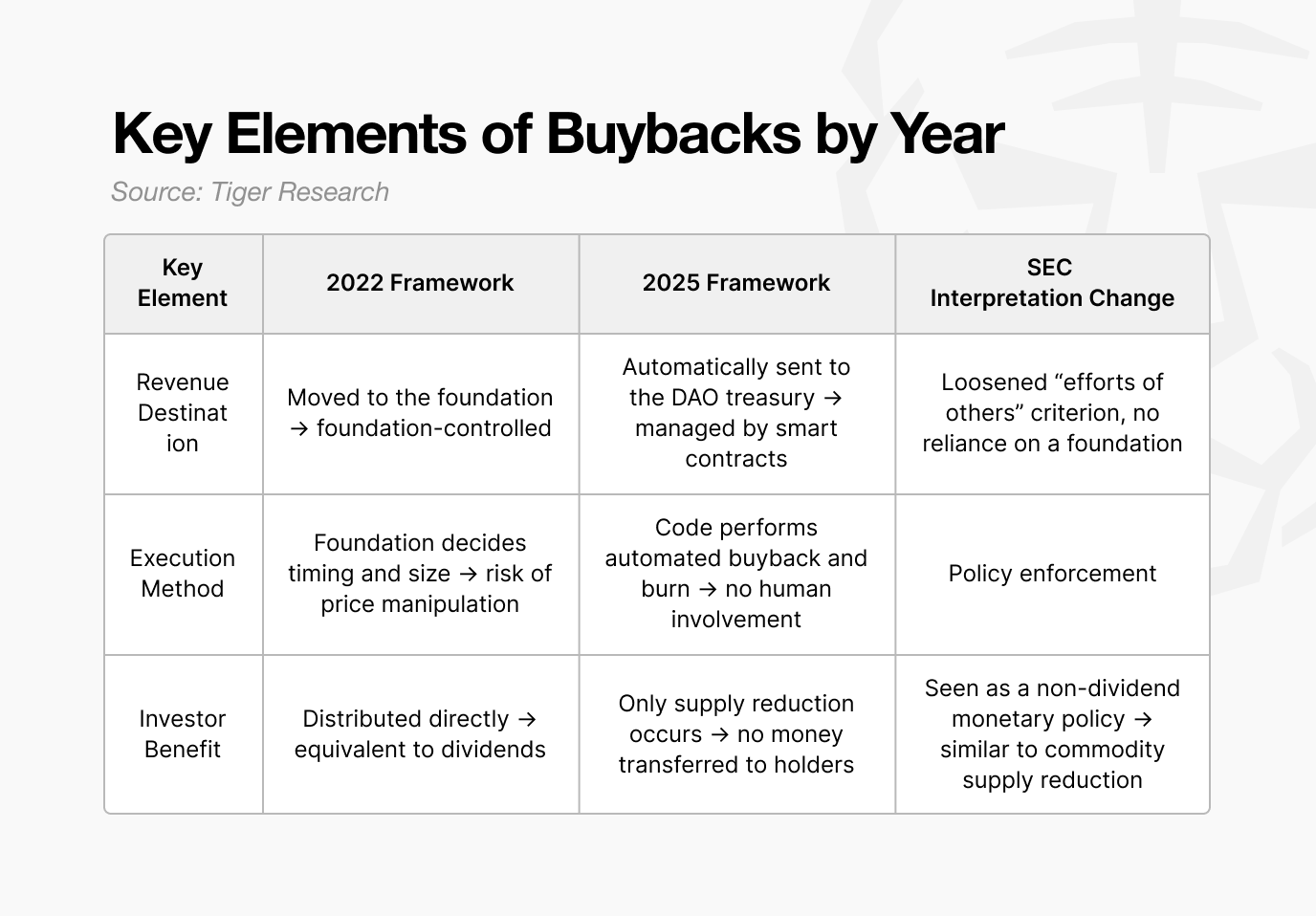

In 2022, the SEC viewed buybacks as an activity subject to securities regulation. When a protocol used its revenue to repurchase its own token, the SEC considered it an economic benefit to token holders, essentially equivalent to a dividend. Because dividend distribution is a core feature of a security, any token conducting buybacks could be classified as a security.

As a result, major projects such as Uniswap either postponed their buyback plans or halted discussions altogether. There was little reason to take on direct regulatory risk.

By 2025, however, the landscape has shifted.

Uniswap has reopened its buyback discussion, and several protocols including Hyperliquid and Pump.fun have already executed buyback programs. What was considered unworkable only a few years ago has now become a trend. So, what changed?

This report examines why buybacks were halted, how regulations and structural models have evolved, and how each protocol’s approach differs today.

2. Why Buybacks Disappeared: The SEC’s Securities Interpretation

The disappearance of buybacks was directly tied to the SEC’s view on securities. From 2021 to 2024, regulatory uncertainty across the crypto sector was unusually high.

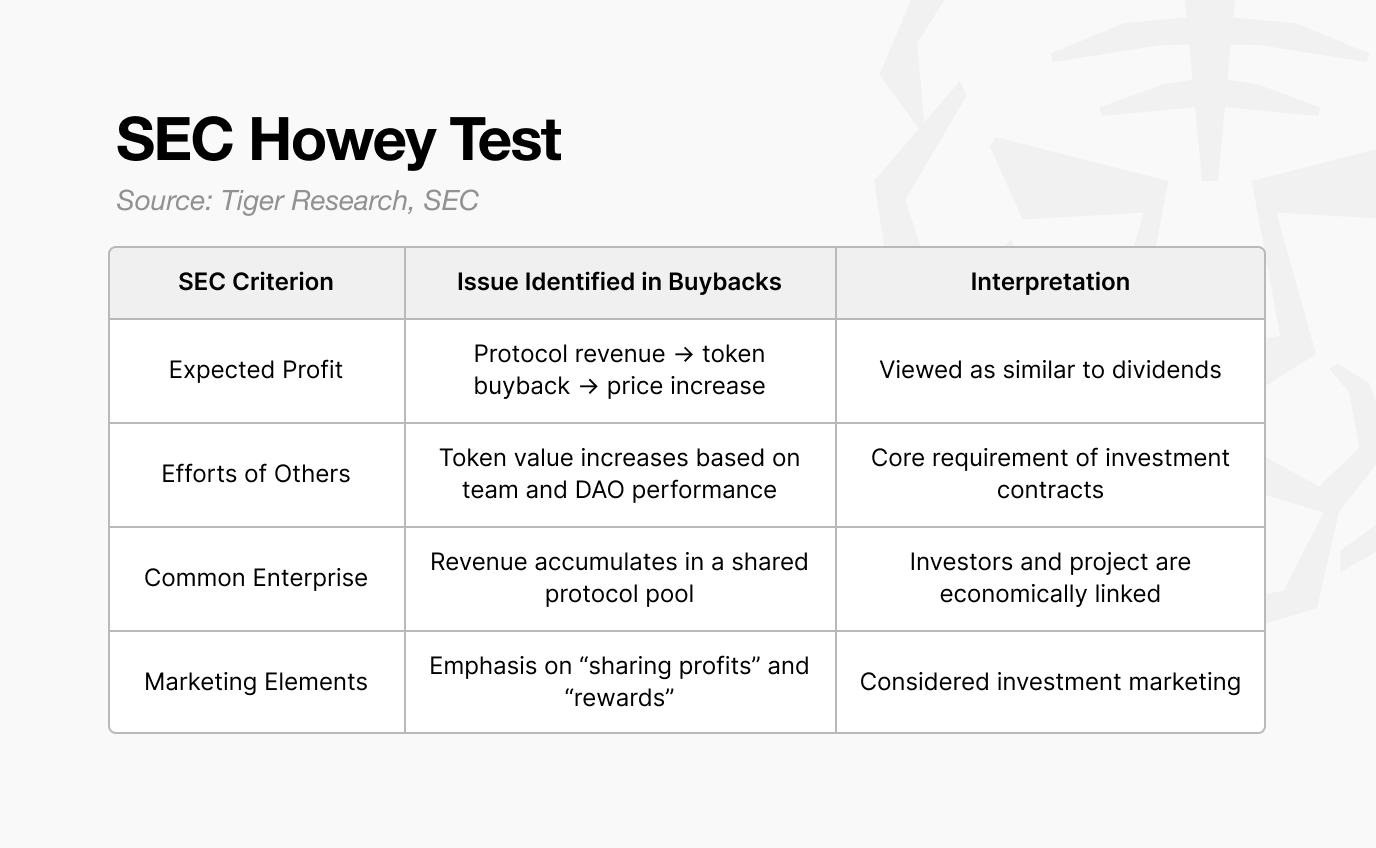

The Howey Test is the framework the SEC uses to determine whether an action constitutes a security. It consists of four elements, and meeting all of them qualifies an asset as an investment contract.

Based on this test, the SEC repeatedly argued that many crypto assets fell under the category of investment contracts. Buybacks were interpreted within the same logic. As regulatory pressure increased across the market, most protocols had little choice but to abandon plans for implementing buybacks.

SEC did not view buybacks as a simple tokenomics mechanism. In most models, a protocol used its revenue to repurchase tokens and then distributed value to token holders or ecosystem contributors. To the SEC, this resembled dividends or shareholder distributions following a corporate buyback.

As the four elements of the Howey Test aligned with this structure, the interpretation of “buybacks = investment contracts” became increasingly entrenched. This pressure was most acute for large, U.S.-based protocols.

Uniswap and Compound, both operated by U.S. teams, came under direct regulatory scrutiny. As a result, they had to be highly cautious when designing token economics and any form of revenue allocation. Uniswap’s fee switch, for instance, remained inactive after 2021.

Due to regulatory risk, major protocols avoided any mechanism that directly distributed revenue to token holders or could materially influence token price. Terms such as “price appreciation” or “profit sharing” were also removed from public communication and marketing.

3. Shift in the SEC’s View: Project Crypto

Strictly speaking, the SEC did not “approve” buybacks in 2025. What changed was its interpretation of what constitutes security.

Gensler: Outcome- and conduct-based (How was the token sold? Does the foundation distribute value directly?)

Atkins: Structure- and control-based (Is the system decentralized? Who actually controls it?)

Under Gensler in 2022, the SEC emphasized outcomes and conduct. If revenue was shared, the token leaned toward being a security. If a foundation intervened in ways that influenced price, it was also treated as a security.

By 2025, under Atkins, the framework shifted toward structure and control. The focus moved to who governs the system and whether operations rely on human decisions or automated code. In short, the SEC began assessing the actual level of decentralization.

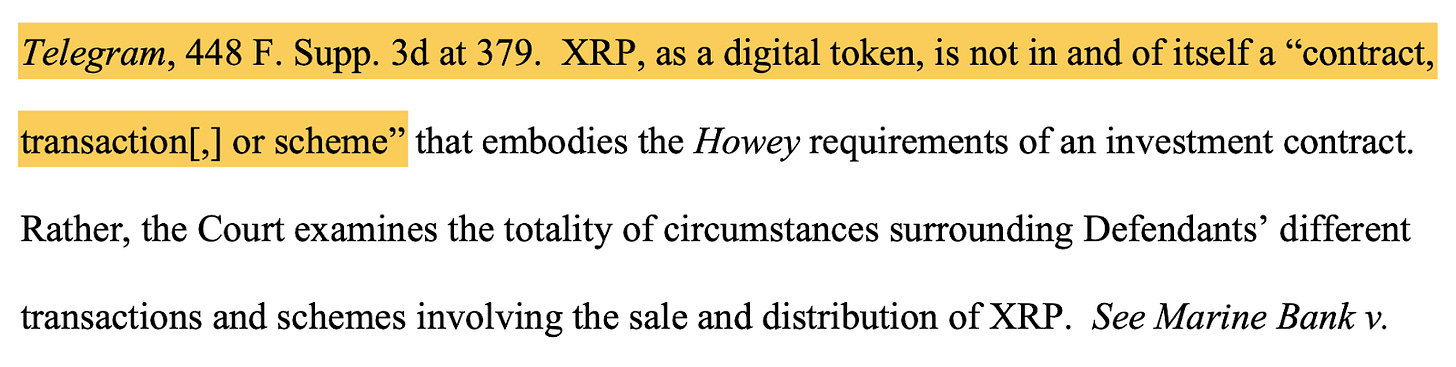

The Ripple (XRP) lawsuit became a critical precedent.

In 2023, the court ruled that XRP sold to institutional investors qualified as a security, while XRP traded on exchanges by retail investors did not. The same token could fall under different classifications depending on how it was sold. This strengthened the interpretation that securities status depends not on the token itself but on the method of sale and the operational structure, a perspective that directly affected how buyback models were evaluated.

These shifts were later consolidated under the initiative known as Project Crypto. After Project Crypto, the SEC’s core questions changed:

Who actually controls the network? Are decisions made by a foundation or by DAO governance? Are revenue distribution and token burns manually timed, or executed automatically by code?

In other words, the SEC began examining substantive decentralization, not superficial structures. Two changes in perspective became especially central.

Lifecycle

Functional Decentralization

3.1. Lifecycle

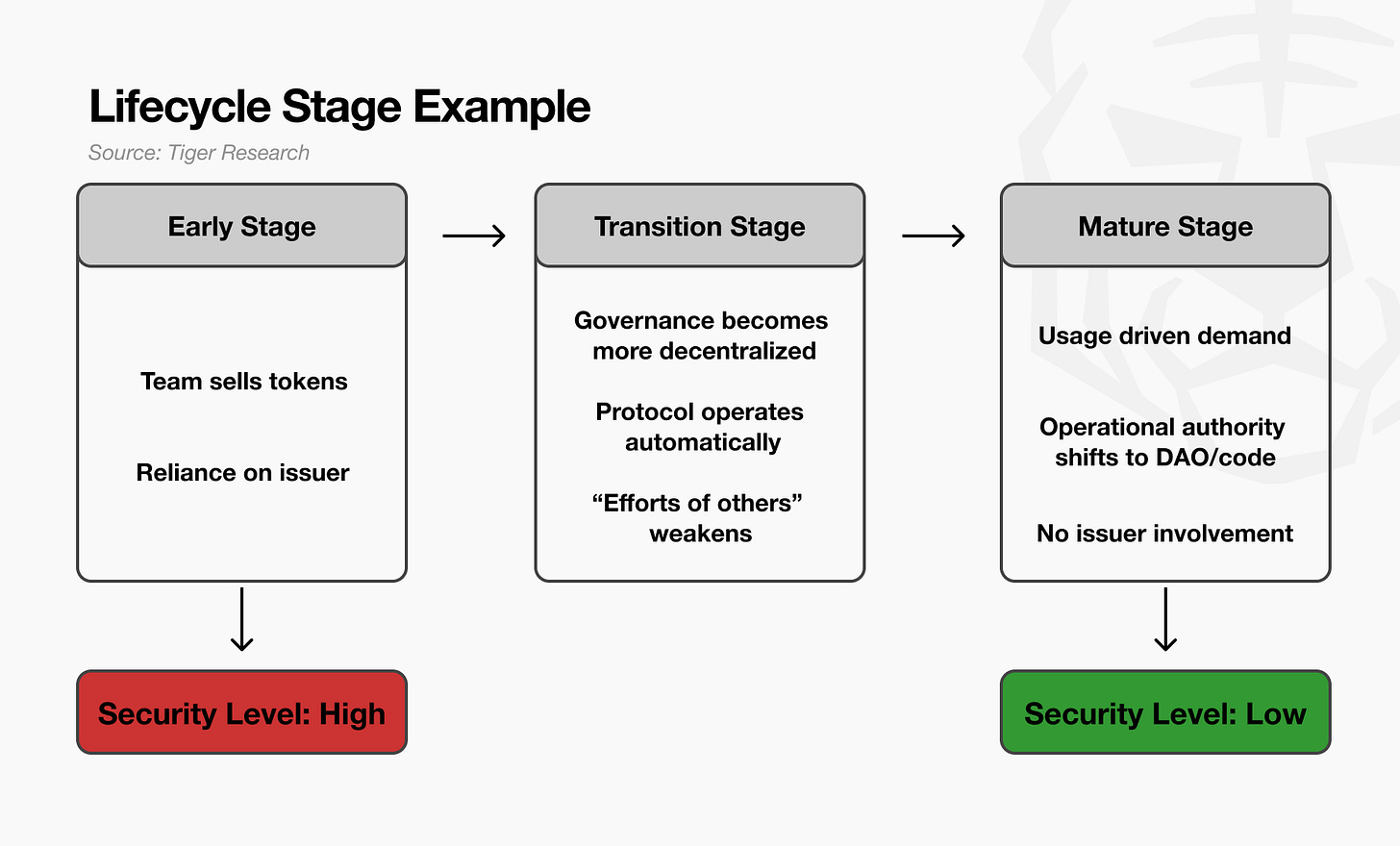

The first shift is the introduction of the token lifecycle perspective.

The SEC no longer treats a token as a permanent security or a permanent non-security. Instead, it recognizes that a token’s legal character can change over time.

For example, In the early stage of a project, the team sells tokens to raise capital, and investors buy them with the expectation that strong execution by the team will increase token value. At this point, the structure relies heavily on the team’s efforts, which makes the sale functionally similar to a traditional investment contract.

As the network begins to see real usage, governance becomes more decentralized, and the protocol operates reliably without direct team intervention, the interpretation shifts. Price formation and system operations no longer depend on the team’s ability or ongoing work. The “reliance on the efforts of others,” a key element in the SEC’s assessment, weakens. The SEC describes this period as the transition phase.

Finally, when the network reaches a mature stage, the character of the token differs significantly from its early phase. Demand is driven more by actual usage than speculation, and the token functions more like a network commodity. At this point, applying traditional securities logic becomes difficult.

In short, the SEC’s lifecycle perspective recognizes that a token may resemble an investment contract in its early phase, but as the network becomes decentralized and self-sustaining, it becomes harder to classify it as a security.

3.2. Functional Decentralization

The second axis is functional decentralization. This perspective focuses not on how many nodes exist, but on who actually holds control.

For example, a protocol may operate across ten thousand nodes worldwide, with its DAO tokens distributed among tens of thousands of holders. On the surface, it appears fully decentralized.

However, if upgrade authority for the smart contracts is held by a three-person foundation multisig, if the treasury is controlled by foundation wallets, and if fee parameters can be changed directly by the foundation, the SEC does not view this as decentralization. In practice, the foundation controls the entire system.

In contrast, even if a network operates with only one hundred nodes, the SEC may view it as more decentralized if all major decisions require DAO voting, if the results are executed automatically by code, and if the foundation cannot intervene at its discretion.

4. Clarity Act

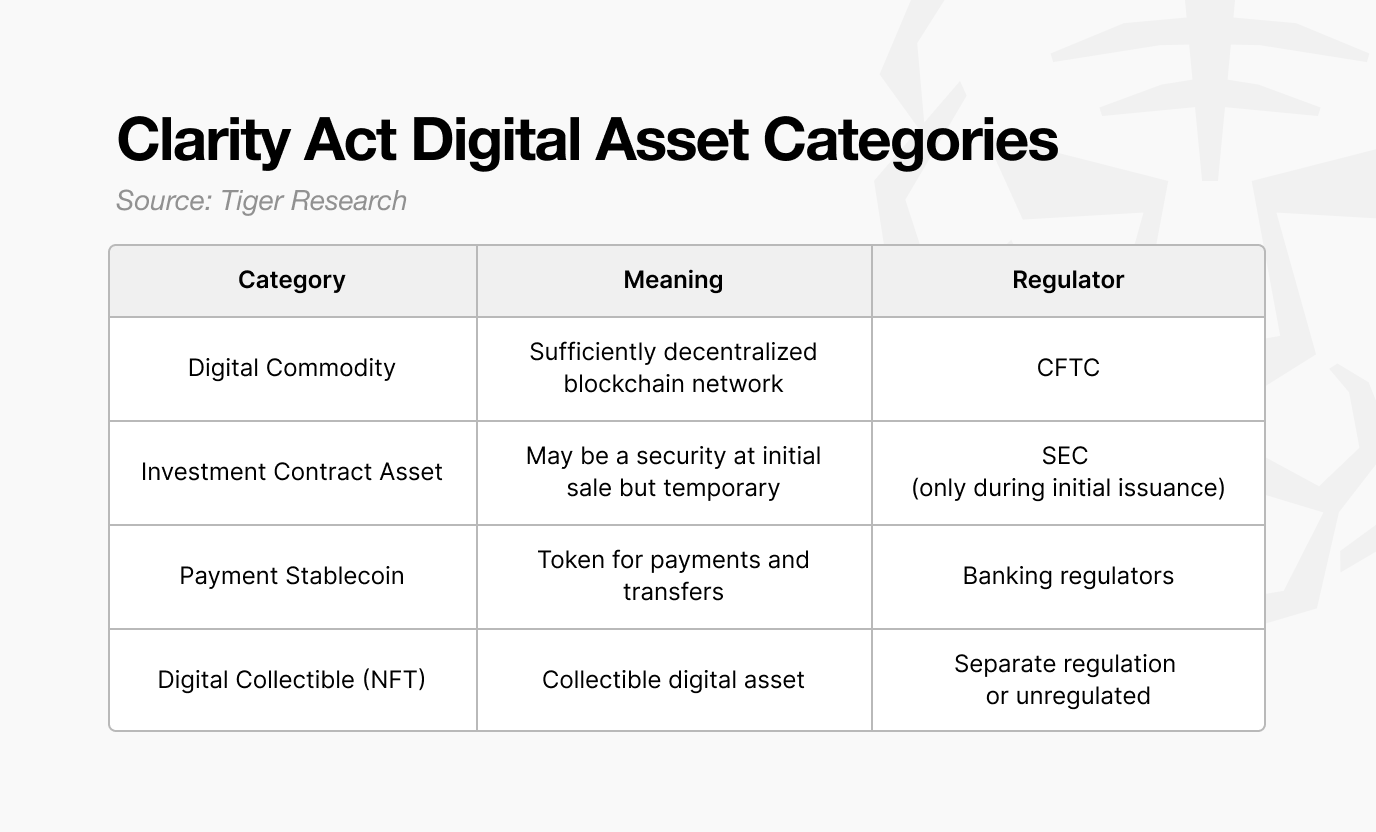

In 2025, another factor that allowed buyback discussions to re-emerge was the Clarity Act, a legislative initiative introduced in the U.S. Congress. The act aims to redefine how tokens should be classified under the law.

While the SEC’s Project Crypto focused on determining which tokens qualify as securities, the Clarity Act asks a more fundamental question: What is a token as a legal asset?

The core principle is straightforward: a token is not permanently a security simply because it was sold under an investment contract. This concept resembles the SEC’s lifecycle approach but applies it differently.

Under the SEC’s previous interpretation, if a token was sold as part of an ICO investment contract, the token itself could continue to be treated as a security indefinitely.

The Clarity Act separates these elements. If a token is sold under an investment contract at issuance, it is treated as an Investment Contract Asset during that moment. But once it enters secondary markets and is traded by retail users, it is reclassified as a Digital Commodity.

In simple terms, a token may be a security at issuance but becomes an ordinary digital asset once it is sufficiently distributed and actively traded.

This classification matters because it changes the regulatory authority. Initial sales fall under SEC oversight, while secondary market activity falls under the CFTC. As oversight shifts, protocols face fewer constraints tied to securities regulation when designing their economic structures.

This shift directly affects how buybacks are interpreted. If a token is classified as a digital commodity in secondary markets, a buyback is no longer viewed as a “security-like dividend.” Instead, it can be interpreted as supply management, similar to monetary policy in a commodity-based system. It becomes a mechanism for operating the token economy rather than distributing profit to investors.

Ultimately, the Clarity Act formalizes the idea that a token’s legal character can change depending on context, and this reduces the structural regulatory burden associated with buyback design.

5. Shift Toward Buyback & Burn

In 2025, buybacks reappeared in combination with automated burn mechanisms. In this model, revenue is not distributed directly to token holders, the foundation has no control over price or supply, and the burn process is executed algorithmically. As a result, the structure is further removed from the elements regulators had previously flagged.

The Unification Proposal announced by Uniswap in November 2025 illustrates this shift clearly.

Under this model, a portion of trading fees is automatically allocated to the DAO treasury, but no revenue is distributed directly to UNI holders. Instead, a smart contract purchases UNI on the open market and burns it, reducing supply and indirectly supporting value. All decisions governing this process are made through DAO voting, with no intervention from the Uniswap Foundation.

The key change is in how the action is interpreted.

Earlier buybacks were viewed as a form of “profit distribution” to investors. The 2025 model reframes the mechanism as supply adjustment, operating as part of network policy rather than a deliberate attempt to influence price.

This structure does not conflict with the SEC’s 2022 view and aligns with the Digital Commodity classification defined in the Clarity Act. Once a token is treated as a commodity rather than a security, adjusting supply resembles a monetary policy tool, not a dividend-like payout.

In its proposal, the Uniswap Foundation stated that “this climate has changed” and that “regulatory clarity in the United States is evolving.” The key insight here is that regulators did not explicitly authorize buybacks. Rather, clearer regulatory boundaries have allowed protocols to design models that satisfy compliance expectations.

In the past, any form of buyback was considered a regulatory risk. By 2025, the question shifted from whether buybacks are allowed to whether their design can avoid triggering securities concerns.

This shift opened space for protocols to implement buybacks within a compliant framework.

6. Protocols Implementing Buybacks

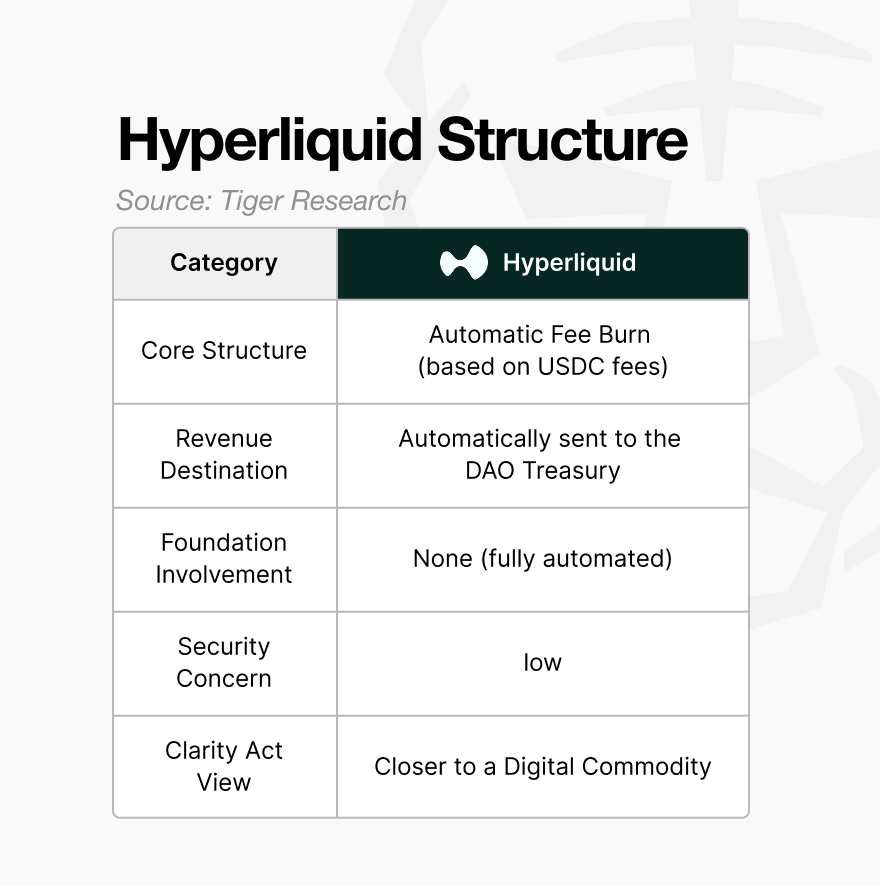

A representative example of protocols that executed buyback-and-burn mechanisms in 2025 is Hyperliquid. Its structure illustrates several defining features:

Automated mechanism: Buybacks and burns operate based on protocol rules, not foundation discretion.

Non-foundation revenue flow: Revenue does not flow into foundation-controlled wallets, or if it does, the foundation cannot use it to influence price.

No direct fee sharing: Revenue is not paid out to token holders. It is used only for supply adjustment or network operating costs.

The key point is that the model no longer promises direct economic benefits to token holders. It functions as a supply policy for the network. The mechanism is redesigned to fit within the boundaries regulators are willing to accept.

However, this does not mean all buybacks are safe.

While buybacks have regained momentum, not every implementation carries the same regulatory risk. The regulatory shifts in 2025 opened the door for structurally compliant buybacks, not for discretionary, one-off, or foundation-driven programs.

The SEC’s logic remains consistent:

If the foundation determines the timing of market purchases, it strengthens the interpretation of “intentional price support.”

Even with DAO voting, if upgrade or execution authority ultimately sits with the foundation, decentralization is not satisfied.

If value accrues to specific holders rather than being burned, it resembles a dividend.

If revenue flows from the foundation to market purchases and then to price appreciation, it reinforces investor expectations and aligns with the elements of the Howey Test.

In short, a buyback that is discretionary, episodic, or foundation-controlled still cannot escape securities scrutiny.

It is also important to note that buybacks do not guarantee price appreciation. Burning reduces supply, but it is only a long-term tokenomics mechanism. Burns do not make a weak project strong; rather, strong projects can strengthen their fundamentals through well-designed burn systems.

🐯 More from Tiger Research

Read more reports related to this research.Disclaimer

This report has been prepared based on materials believed to be reliable. However, we do not expressly or impliedly warrant the accuracy, completeness, and suitability of the information. We disclaim any liability for any losses arising from the use of this report or its contents. The conclusions and recommendations in this report are based on information available at the time of preparation and are subject to change without notice. All projects, estimates, forecasts, objectives, opinions, and views expressed in this report are subject to change without notice and may differ from or be contrary to the opinions of others or other organizations.

This document is for informational purposes only and should not be considered legal, business, investment, or tax advice. Any references to securities or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only and do not constitute an investment recommendation or an offer to provide investment advisory services. This material is not directed at investors or potential investors.

Terms of Usage

Tiger Research allows the fair use of its reports. ‘Fair use’ is a principle that broadly permits the use of specific content for public interest purposes, as long as it doesn’t harm the commercial value of the material. If the use aligns with the purpose of fair use, the reports can be utilized without prior permission. However, when citing Tiger Research’s reports, it is mandatory to 1) clearly state ‘Tiger Research’ as the source, 2) include the Tiger Research logo. If the material is to be restructured and published, separate negotiations are required. Unauthorized use of the reports may result in legal action.