Competition between the National Assembly and government ministries over who should issue KRW-backed stablecoins has intensified. This report clarifies the background behind the delayed legislation and examines the key players currently shaping the debate.

KeyTakeways

Bank vs non-bank issuance conflict and regulatory turf wars have stalled legislation.

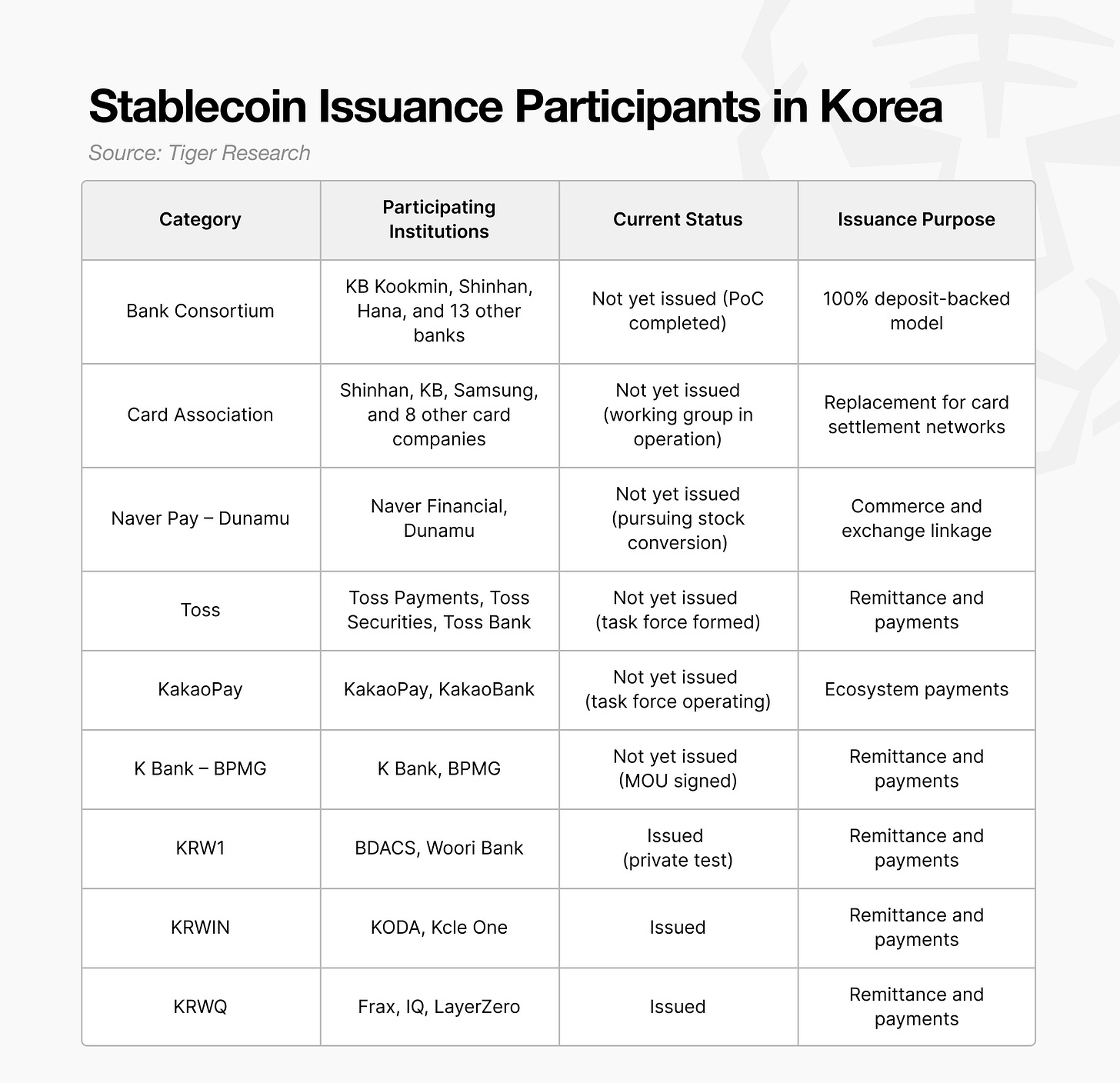

BDACS-Woori Bank (Avalanche), Naver-Dunamu, and Frax-IQ are testing won-backed stablecoins.

No clear path exists yet. Korea must build a sandbox and design its own model.

1. Market Moves Ahead Amid Regulatory Delays

Discussions around KRW stablecoins have been ongoing in Korea since the broader rise of the stablecoin era. Initially, the Bank of Korea chose to focus on developing a CBDC rather than supporting stablecoins.

After the CBDC initiative was suspended, policy attention shifted back toward the stablecoin model. However, persistent differences among government ministries have continued to delay legislative progress.

Meanwhile, the market has moved ahead of regulation. Domestic private firms and foreign companies have begun issuing KRW-backed stablecoins on global chains such as Solana and Base, seeking early positioning in anticipation of eventual regulatory clarity.

2. Major Competitors in the KRW Stablecoin Market

Most projects, except for the bank consortium, remain in the planning or temporary task force stage.

Among them, the Naver Pay–Dunamu partnership has drawn significant attention in Korea. This is largely due to speculation that Dunamu’s blockchain network, Kiwa Chain, could be used to issue a stablecoin, and that Naver’s existing infrastructure including its shopping and payment systems could provide real-world utility for KRW stablecoin transactions.

Some initiatives have progressed beyond the conceptual phase. The BDACS–Woori Bank consortium, for example, has built a framework that mirrors traditional finance: all user deposits are held in trust accounts at banks, protected by deposit insurance, ensuring a comparable level of stability and oversight. The consortium has already deployed its KRW stablecoin, KRW1, on the Avalanche network, and is conducting additional testing on Circle’s ARC network.

3. Core Legislative Divide: Non-Bank vs. Bank Issuers

The main reason for Korea’s slow progress on KRW stablecoin regulation is the legislative divide. Current proposals fall into two opposing camps: non-bank and bank-based frameworks.

At the heart of the debate are two fundamental questions:

Should stablecoins be classified as “currency” or as “digital assets”?

Should private issuers be allowed to issue stablecoins, or should this authority be limited to banks?

If stablecoins are treated as digital assets, regulatory barriers are lower and market innovation could accelerate but concerns over monetary stability increase. Conversely, restricting issuance to banks enhances systemic safety but limits flexibility and innovation. This tension between innovation and stability has kept the legislative process gridlocked.

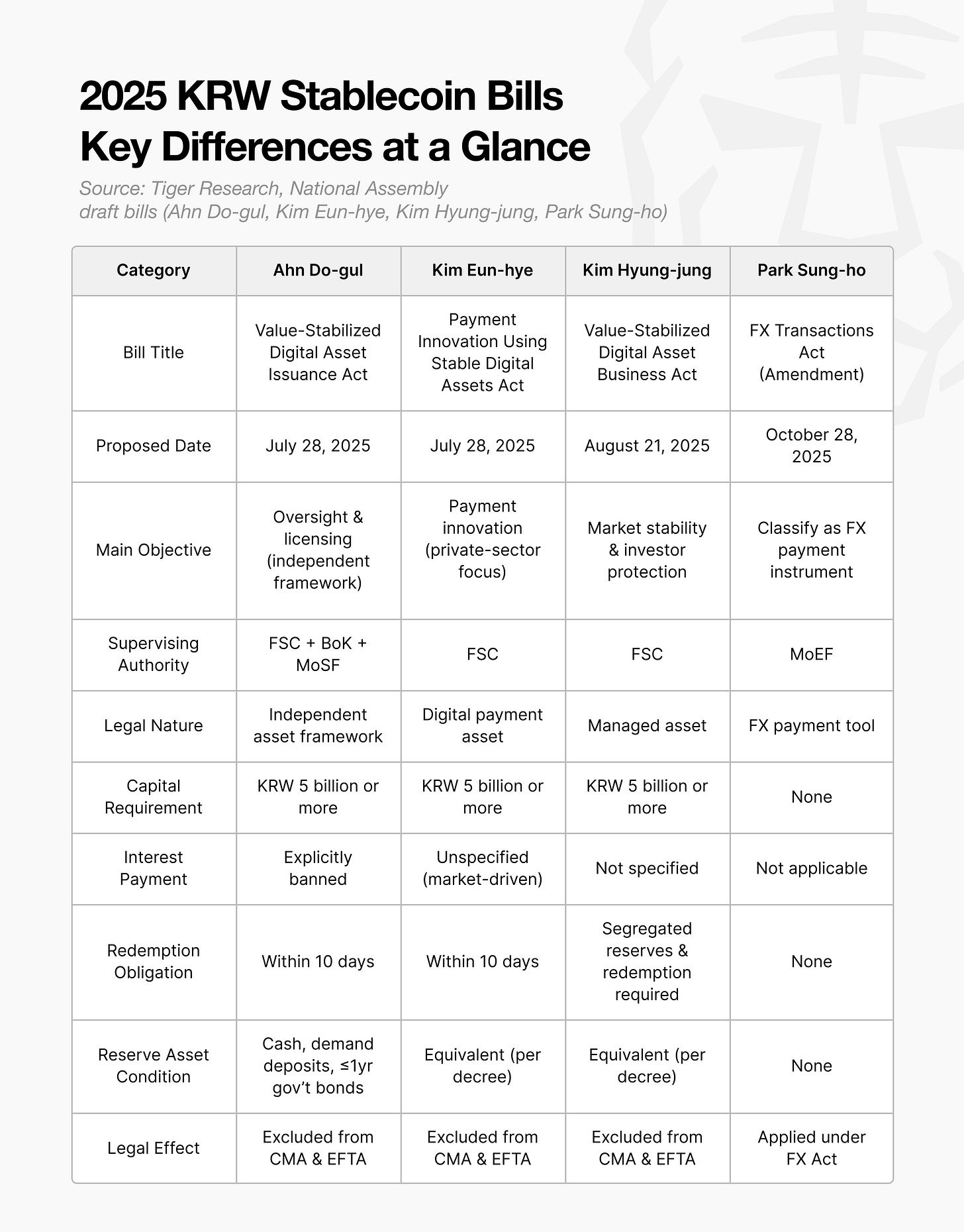

3.1. Non-Bank Proposals (Ahn Do-gul, Kim Eun-hye, Kim Hyung-jung)

The non-bank bills define KRW stablecoins as a type of digital asset, comparable to securities such as stocks or bonds. This classification allows private entities to issue and trade them under financial market supervision.

Issuers must hold at least KRW 5 billion in capital and maintain 100% collateral reserves in safe assets. Oversight falls under the Financial Services Commission (FSC), which seeks to encourage private-sector innovation while enforcing consumer protection rules. In this model, stablecoins function as financial instruments within the broader digital asset market rather than as extensions of the national currency.

3.2. Bank Proposal (Park Sung-ho)

The bank-based bill, in contrast, classifies KRW stablecoins as part of the national currency system not as digital assets. The framework aims to preserve monetary sovereignty and maintain the stability of the won.

Under this proposal, management authority is shared between the Ministry of Economy and Finance and the Bank of Korea. Stablecoin issuance would be restricted to a limited number of designated banks, and all transactions must occur through registered exchanges and remittance institutions.

Cross-border transfers require foreign exchange reporting, and stablecoins may only be used within government-approved financial networks and payment systems. The bill focuses on preventing money laundering, tax evasion, and illicit capital flows, positioning bank-issued stablecoins as an extension of Korea’s regulated financial infrastructure.

4. Inter-Agency Conflict: Who Should Regulate?

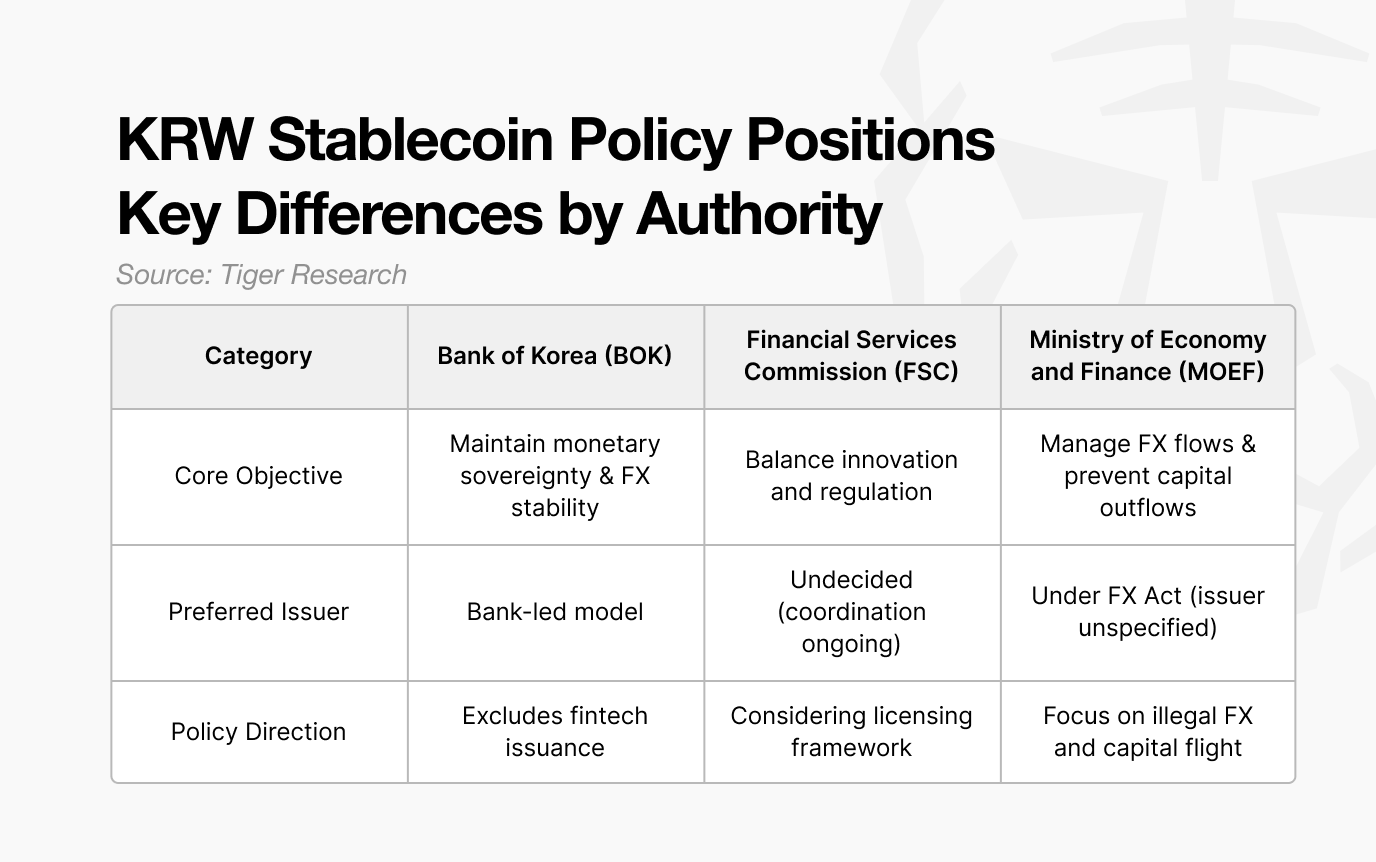

One of the main reasons for the delay in legislation is the jurisdictional conflict among government agencies. Beyond policy debates, the core issue is which institution will hold regulatory authority over KRW stablecoins.

The Bank of Korea (BOK) argues that issuance should remain bank-centered, citing the need to protect monetary sovereignty and ensure currency stability. The Ministry of Economy and Finance (MOEF) prioritizes foreign exchange control, seeking to incorporate stablecoins into the Foreign Exchange Transactions Act to manage capital flows and prevent outflows. Meanwhile, the Financial Services Commission (FSC) has signaled plans to introduce a licensing regime, but detailed standards are still under negotiation among ministries.

This kind of jurisdictional struggle is not new in Korea’s financial system. Each time a new payment or settlement infrastructure emerges, agencies have competed for supervisory control. A similar dispute occurred during the 2020 amendment of the Electronic Financial Transactions Act:

The BOK insisted that big tech payment systems fall under its oversight to safeguard payment stability.

The FSC countered that electronic financial services should be regulated within the broader framework of financial stability and consumer protection.

In the end, both agencies’ roles were partially reflected in the law through shared oversight provisions.

A comparable overlap occurred again in 2024–2025, when the FSC assumed authority over digital asset regulation, while the Financial Supervisory Service (FSS) created a separate division to handle the same domain prompting criticism that “two agencies oversee one industry.”

Control over supervision carries significant implications: it determines budget allocation, staffing authority, international coordination rights, and policy leadership within the sector. Given that KRW stablecoins encompass both domestic payment systems and foreign exchange transactions, the stakes are even higher than in previous regulatory disputes.

5. There is no single right answer

Where should it be used?

Will it accelerate capital outflows?

Should issuance be limited to banks?

Which government agency should oversee it?

There are no definitive answers to any of these questions.

Other countries have already completed legislation or are in the final stages. Korea no longer has time for purely theoretical debate. The most practical path forward is to run market experiments through regulatory sandboxes, accumulate real-world usage data, and design a Korean won stablecoin framework based on those findings.

🐯 More from Tiger Research

Read more reports related to this research.Disclaimer

This report has been prepared based on materials believed to be reliable. However, we do not expressly or impliedly warrant the accuracy, completeness, and suitability of the information. We disclaim any liability for any losses arising from the use of this report or its contents. The conclusions and recommendations in this report are based on information available at the time of preparation and are subject to change without notice. All projects, estimates, forecasts, objectives, opinions, and views expressed in this report are subject to change without notice and may differ from or be contrary to the opinions of others or other organizations.

This document is for informational purposes only and should not be considered legal, business, investment, or tax advice. Any references to securities or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only and do not constitute an investment recommendation or an offer to provide investment advisory services. This material is not directed at investors or potential investors.

Terms of Usage

Tiger Research allows the fair use of its reports. ‘Fair use’ is a principle that broadly permits the use of specific content for public interest purposes, as long as it doesn’t harm the commercial value of the material. If the use aligns with the purpose of fair use, the reports can be utilized without prior permission. However, when citing Tiger Research’s reports, it is mandatory to 1) clearly state ‘Tiger Research’ as the source, 2) include the Tiger Research logo. If the material is to be restructured and published, separate negotiations are required. Unauthorized use of the reports may result in legal action.