This report was written by Tiger Research, analyzing Vietnam’s new crypto exchange licensing framework requiring $380M minimum capital and the competition between global players like Binance and Bybit versus local institutions for limited licenses.

TL;DR

Vietnam’s new framework sets extremely high entry barriers, making licensing viable only for large banks, securities firms, or global exchanges with strong partners.

Seven local firms have positioned themselves, but most lack the capital and institutional depth to qualify.

Binance and Bybit have already met with top government leaders, suggesting foreign names will secure a place alongside a small number of domestic licensees.

1. Vietnam’s Market Shift: Moving Under Regulatory Oversight

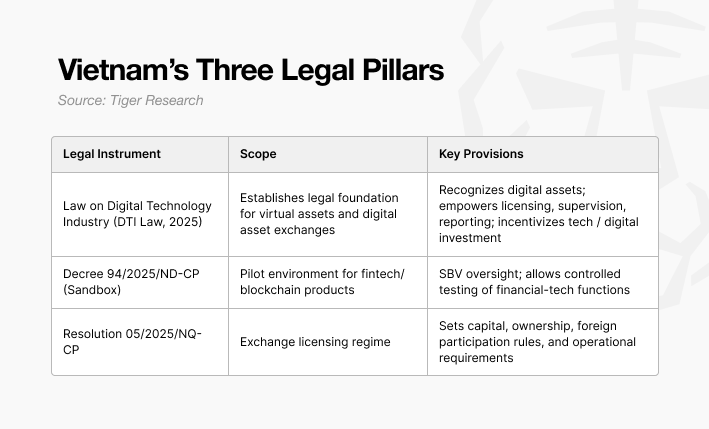

Vietnam’s digital asset market entered a decisive transition in 2025. After years of regulatory ambiguity, the government introduced a three-part framework that collectively moves the country from a permissive “gray zone” into a supervised, tax-capturable regime.

The first pillar is the Law on Digital Technology Industry (DTI Law), passed by the National Assembly in June 2025 and scheduled to take full effect on January 1, 2026. For the first time, digital assets are explicitly recognized in law, separate from securities and fiat instruments. The DTI Law provides a statutory foundation for taxation, AML requirements, and supervisory powers that will be clarified in implementing decrees.

The second development is the Sandbox Decree (No. 94/2025/NĐ-CP), effective from July 1, 2025. Managed by the State Bank of Vietnam (SBV), the sandbox establishes a controlled mechanism for testing innovations in banking and finance. Although broader than crypto, the sandbox is expected to intersect with exchange licensing through AML, KYC, and settlement requirements.

The third and most immediate policy move is the government’s Resolution 05/2025/NQ-CP, issued on September 9, 2025, which launched a five-year pilot program for the issuance and trading of virtual assets. This pilot is the first practical framework under which exchanges can operate legally in Vietnam. Crucially, the resolution stipulates that only Vietnamese enterprises may be licensed as operators in the pilot phase. Foreign exchanges can therefore participate only through joint ventures or by supplying technology, compliance systems, and liquidity.

Taken together, these measures signal the government’s intent to gradually re-onshore digital asset activity under strict oversight. The policy direction favors domestic control, alignment with Financial Action Task Force (FATF) standards, and integration with Vietnam’s broader ambitions to develop regional financial centers like Da Nang.

From an institutional perspective, the key point is that Vietnam is no longer an unregulated market, which is a positive step. However, the high licensing hurdles and restrictions on foreign participation indicate only limited openness. The next 12 to 18 months will determine whether Vietnam emerges as a structurally attractive market or remains a temporary policy experiment.

2. High Licensing Barriers for Operating Under Regulation

Resolution No. 05/2025/NQ-CP, issued on September 9, 2025, sets strict entry conditions for service providers in Vietnam’s five-year pilot for crypto issuance and trading. Only Vietnamese enterprises are eligible to apply for operator licenses, with incorporation required under the Law on Enterprises.

Licensed entities must maintain a minimum charter capital of VND 10 trillion (approximately USD 380 million), fully contributed in Vietnamese dong. At least 65 percent of this capital must come from institutional shareholders, and within that share, more than 35 percent must be contributed by at least two organizations drawn from the following categories: commercial banks, securities companies, fund management companies, insurance companies, or technology enterprises. Institutional shareholders must also demonstrate two consecutive years of profitable operations prior to application, with financial statements audited and receiving unqualified opinions in both years.

Foreign ownership is capped at 49 percent of charter capital, ensuring that licensed operators remain under domestic control. In addition, licensed providers must satisfy strict human-capital and infrastructure requirements, including a chief executive with at least two years of financial-sector experience, a chief technology officer with at least five years of relevant IT experience, and staffing of at least ten employees with cybersecurity certifications and another ten with securities practitioner licenses. Technology systems must meet Information Security Level 4, the highest domestic standard for financial services.

The licensing framework signals the government’s intent to expand the regulated crypto market, but the requirements are demanding even for established financial institutions. Applied to exchanges, the thresholds are already high; if extended to wallet services, GameFi projects, or mid-sized exchanges, most crypto-native firms would be unable to qualify.

Notably, Vietnam-origin projects such as KyberSwap and Coin98 have suspended domestic operations. In practice, a hybrid model is likely to emerge: banks, securities firms, insurers, and large technology companies will form the licensed core, while Web3 projects participate primarily as technology and service providers. This dynamic shifts market control to regulated institutions, pushing startups and crypto-native firms outside the licensing perimeter.

The framework also restricts activities to asset-backed token issuance and spot trading, with settlement limited to Vietnamese dong. The use of crypto as a payment method remains prohibited, while derivatives and margin trading are excluded. Compared with early movers such as the United States, Singapore, and Hong Kong, Vietnam’s regime permits only a narrow scope of business.

3. Market Participants (Local vs Global)

3.1. Local Participants

Several Vietnamese firms have already established companies branded as “digital asset exchanges” in anticipation of Vietnam’s new licensing framework. These entities represent the domestic contenders most likely to compete for official approval once the regime takes effect. However, their current capitalization levels and shareholder structures remain far from the stringent requirements outlined in Resolution 05/2025.

For institutional readers, three observations stand out. First, the capital gap is decisive. All of the current entrants are capitalized at levels ranging from VND 2 billion to VND 1,470 billion, far short of the statutory minimum of VND 10 trillion. Without large-scale injections from banks, securities firms, or insurers, most of these entities will not qualify for licensing.

Second, institutional anchoring will determine who survives. The Resolution requires at least 65 percent institutional ownership, including 35 percent from at least two banks, securities firms, insurers, or technology enterprises. This provision clearly favors players already tied to major financial institutions such as SSI, VIX, Techcom, HD, and MB, while leaving fintech-led vehicles like DNEX or CAEX at a disadvantage unless they can attract stronger partners.

Finally, market expectations suggest that licenses will be limited. Rumors indicate that no more than five operators will be approved in the initial phase. With at least seven contenders already positioning themselves, some will inevitably be excluded. For global exchanges evaluating Vietnam, this raises the importance of aligning early with the most credible domestic partners.

3.2. Global Participants and Government Engagement

Global exchanges are moving early to establish relationships with Vietnamese authorities. On September 24, 2025, during an official visit to the UAE, Permanent Deputy Prime Minister Nguyễn Hòa Bình met with Richard Teng, CEO of Binance. The Deputy Prime Minister invited Binance to establish a headquarters in Da Nang and to cooperate with Vietnam’s planned International Financial Center in deploying a licensed digital asset exchange. He also requested that Teng, who previously led the Abu Dhabi Global Market, serve as a senior advisor to Vietnam’s financial center initiative. This invitation was formally published on the Government’s communication channels, signaling clear policy intent.

At the same time, an MOU was signed between the People’s Committee of Da Nang and Binance, establishing cooperation in blockchain and digital asset development. Binance’s engagement, therefore, has both political endorsement and a local-government partnership framework.

Bybit has also positioned itself strongly. On September 17, 2025, it signed an MOU with the People’s Committee of Da Nang, alongside the Abu Dhabi Blockchain Center (ADBC) and Verichains. The partnership covers liquidity provision, infrastructure security, and ecosystem connectivity, aligning closely with Vietnam’s objectives for its regime. Bybit’s agreement, while not as high-level as Binance’s meeting with the Deputy Prime Minister, gives it a tangible foothold in the IFC narrative.

These moves place Binance and Bybit at the front of the queue among global players. As noted above, speculation points to only five licenses being granted under the regime. If two are effectively reserved for global exchanges, that leaves only three slots for local firms, despite at least seven already competing for recognition. This dynamic heightens competition within Vietnam, as domestic entities will be forced to demonstrate institutional anchoring and scale to secure one of the remaining places.

The positioning of Binance and Bybit also raises a further question: what happens to the other global exchanges that already dominate Vietnam’s retail market, such as BingX and MEXC? These firms maintain significant user bases in Vietnam through offshore platforms, but without early government engagement, they risk being sidelined in the licensed market. Unless they pivot to partnerships with approved local entities or secure invitations similar to Binance and Bybit, their operations will remain outside the regulatory perimeter, potentially vulnerable to future enforcement once the regime begins to absorb market volume.

4. Strategic Scenarios: The GTM Playbook for “CEX Tiger”

What options exist for projects seeking entry into Vietnam under the new regime? Consider a hypothetical case of “CEX Tiger,” a global exchange planning to expand into Vietnam, and what strategies would be most viable.

The first and most important decision is partner selection. Foreign exchanges cannot obtain licenses directly and must align with a strong domestic institution. Identifying which Vietnamese banks, securities firms, or insurers are best positioned to secure one of the limited licenses is critical. The choice of partner will determine market access, compliance posture, and long-term scalability.

Once a partner is secured, the next step is defining the operating model. A hybrid structure is required: the Vietnamese partner holds the license and regulatory responsibility, while CEX Tiger contributes technology, liquidity, and operational expertise. The joint venture becomes the formal entity, with the domestic institution serving as the legal and regulatory front and the foreign exchange running the underlying service.

Business expectations must also be calibrated. The framework restricts activity to spot trading, settlement in Vietnamese dong, and limited investor participation. This is not a market designed for immediate trading volumes or derivative-driven revenue. Instead, the strategic goal should be to secure early presence, establish regulatory goodwill, and build legitimacy ahead of potential future liberalization.

Competition, however, will be intense. If two licenses are allocated to Binance and Bybit, only three would remain for domestic institutions. For late entrants, the real question is not whether Vietnam is attractive—the market’s growth and user base make that clear—but whether a credible domestic partner can be secured, and whether that partner is willing to cooperate. Missing the first licensing round could delay entry until the framework expands.

For exchanges like CEX Tiger, the strategy should be to view Vietnam less as a near-term profit engine and more as a platform for long-term positioning. Success depends on securing the right domestic partner, accepting a minority role, and embedding early in one of Asia’s fastest-growing crypto markets.

From a retail perspective, the challenge is more complex. Vietnamese users are already accustomed to global platforms. Even with a license, a new entrant will face scrutiny over security standards, the breadth of tradable assets, and overall reliability. Licensing brings legitimacy but does not automatically translate into user trust or market share.

Ultimately, exchanges such as CEX Tiger face a strategic choice: enter the competitive licensing race with a domestic partner, or remain outside the regulated perimeter, maintaining their existing user base while monitoring regulatory developments.

🐯 More from Tiger Research

Read more reports related to this research.Vietnam Crypto Market 2025: Complete Analysis of 21 Million Investor

The Hidden Risk in Crypto Markets: What Happens If Telegram Goes Down?

Vietnam’s Crypto Regulation: From Regulatory Gray Zone to Controlled Experimentation

Disclaimer

This report has been prepared based on materials believed to be reliable. However, we do not expressly or impliedly warrant the accuracy, completeness, and suitability of the information. We disclaim any liability for any losses arising from the use of this report or its contents. The conclusions and recommendations in this report are based on information available at the time of preparation and are subject to change without notice. All projects, estimates, forecasts, objectives, opinions, and views expressed in this report are subject to change without notice and may differ from or be contrary to the opinions of others or other organizations.

This document is for informational purposes only and should not be considered legal, business, investment, or tax advice. Any references to securities or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only and do not constitute an investment recommendation or an offer to provide investment advisory services. This material is not directed at investors or potential investors.

Terms of Usage

Tiger Research allows the fair use of its reports. ‘Fair use’ is a principle that broadly permits the use of specific content for public interest purposes, as long as it doesn’t harm the commercial value of the material. If the use aligns with the purpose of fair use, the reports can be utilized without prior permission. However, when citing Tiger Research’s reports, it is mandatory to 1) clearly state ‘Tiger Research’ as the source, 2) include the Tiger Research logo. If the material is to be restructured and published, separate negotiations are required. Unauthorized use of the reports may result in legal action.